The story so far: Last week, Delhi was once again covered in a cascading haze of smog— witnessing very poor air quality, sticking to the trend that has existed during winter months for some years now. The last stage of the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) was activated and then revoked, primary schools closed, and the debate about the “main culprit” for the polluted air was rekindled.

As the situation becomes an annually recurring one, here’s a look at how far back it goes and what policies have been adopted by the Centre and Delhi’s elected governments over the years.

While civil society and media attention for Delhi’s air pollution problem and high PM2.5 concentrations peaked in the last decade, with annual episodes of pollution induced smog setting over the Capital in winter months, air pollution has been on the rise since the 1990s.

In March 1995, the Supreme Court, while hearing a plea by environmentalist and lawyer M.C. Mehta about Delhi’s polluting industries, noted that Delhi was the world’s fourth most polluted city in terms of concentration of suspended particulate matter (SPM) in the ambient atmosphere as per the World Health Organisation’s 1989 report. The Court took note of two polluting factors— vehicles and industries, and in 1996 ordered the closure and relocation of over 1,300 highly-polluting industries from Delhi’s residential areas beyond the National Capital Region (NCR) in a phased manner. Multiple brick kilns were also directed to be relocated outside city limits.

In 1996, Mr. Mehta filed another public interest litigation alleging that vehicular emissions were leading to air pollution and posed a public health hazard. In the same year, a report about Delhi’s air pollution by the Centre for Science and Environment made the apex court take suo motu action, issuing a notice to the Delhi government to submit an action plan to curb pollution. Both matters were later merged.

Later that year, the Delhi government submitted an action plan. The Supreme Court, recognising the need for technical assistance and advice in decision-making and implementation of its orders, asked the Ministry of Environment and Forests (now the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change- MoEFCC) to establish an authority for Delhi, leading to the creation of the Environmental Pollution Control Authority of Delhi NCR (EPCA) in 1998.

The EPCA submitted its report containing a two-year action plan in June of that year and the Supreme Court subsequently ordered the conversion of the whole Delhi Trasport Corporation (DTC) bus fleet, taxis, and autos to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG), and the phasing out of all pre-1990 autos. Other measures between the late 1990s and early 2000s included the complete removal of leaded petrol, removal of 15 and 17-year-old commercial vehicles and a cap of 55,000 on the number of two-stroke engine auto rickshaws (which reports at the time said were contributing to 80% of pollution in the city). Coal-based power plants within Delhi were also later converted to gas-based ones.

Around this time, the Centre also decided to revamp its monitoring programme and establish a network of monitoring stations under the National Air Quality Programme (NAMP) to measure key pollutants. Under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) specified by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), pollutants like PM10 (particulate matter with a diameter exceeding 10 microns), sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides were measured.

The National Ambient Air Quality Standards were revised in 2009 to include 12 categories of pollutants including PM2.5 (diameter under 2.5 microns)— a noxious pollutant which can penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, resulting in cardiovascular and respiratory impacts, and potentially also affecting other organs. Particulate Matter (PM) is primarily generated by fuel combustion in different sectors, including transport, energy, households, industry and agriculture.

Also read: Data | Which major Indian cities exceed WHO’s revised pollution limits?

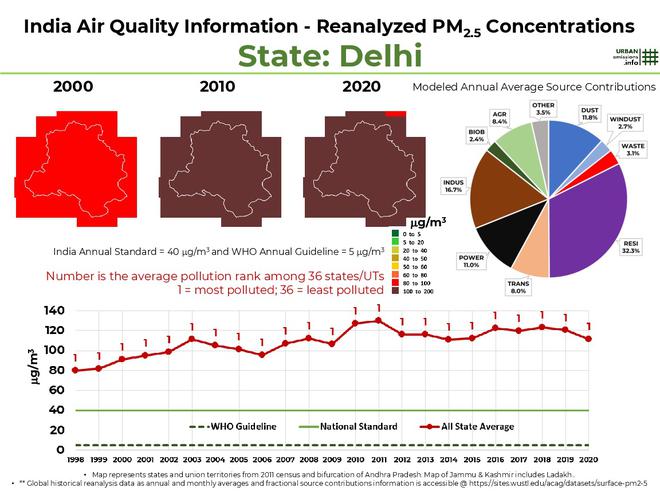

According to the revised NAAQS, the acceptable annual limit for PM2.5 is 40 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m 3) and 60 µg/m 3 for PM10. The renewed WHO standards meanwhile, prescribe an accepted annual average of 5 µg/m 3 for PM2.5 and 15 µg/m 3 for PM10.

While PM2.5 was only included in the Indian standards in 2009, a computer modelling study by UrbanEmissions.Info (an independent three-day forecasting system and information repository on air pollution) reanalysed the pan-India PM2.5 concentration from 1998 to 2020 and found that Delhi was the most polluted in all States/UTs each year through all the 23 years. Delhi’s annual PM2.5 levels increased by 40% from 80 g/m 3 to 111 g/m 3.

Another study by the US-based Health Effects Institute released this year studied data between 2010 and 2019, finding Delhi to be the most polluted city in the world in terms of PM2.5 levels, reporting an average annual exposure (relative to population) of 110 µg/m3.

In January and April 2016, the Delhi government tested the odd-even vehicular rationing rule in two fortnightly windows. In the winter of 2016, Delhi witnessed one of its worst incidents of pollution-induced smog, with PM2.5 and PM10 levels reaching a whopping 999 µg/m 3 in parts of Delhi on November 1, and PM2.5 later dropping to a still very high 750 µg/m 3 from November 8, both several times over acceptable limits.

In November 2016, the Supreme Court told Delhi and NCR authorities to form a plan to deal with air pollution and subsequently the MoEFCC in early 2017 came out with the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), which involved coordination between multiple agencies in Delhi to activate reactive pollution control measures corresponding to increasing Air Quality Index (AQI) levels.

Multiple studies over the years, including the Delhi Pollution Control Committee’s (DPCC) 2019 report by IIT Delhi and Madras experts, found that the rapid growth in Delhi’s population, industrialisation and urbanisation, and increase in the motorised private vehicle fleet have resulted in the increased concentration of pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone.

Between 2001 and 2011, Delhi saw a population spurt from 1.378 crore to 1.678 crore. As of 2011, the population of Delhi and NCR was 25.8 million or 7.6% of India’s urban population. While Delhi’s total area is 1,483 square kilometres (km 2), the population density grew from 9,340 persons per km 2 in 2001 to 11,320 persons per km 2 in 2011. From around 4.2 million motor vehicles registered in 2004 in Delhi alone, the registered vehicles increased to around 10.9 million in March 2018.

While multiple polluting industries were moved out of Delhi in the 1990s, it still has one of the biggest clusters of small-scale industries. The CPCB notes that several of Delhi’s polluting industrial clusters do not meet air, water, and soil standards. The Najafgarh drain basin, which houses multiple industrial areas, is the most polluted cluster in India with its air and water being in the ‘critical’ category. Over 3,100 industries are located across NCR.

There have been various studies attributing percentages to each source contributing to Delhi’s PM2.5 levels—vehicular emissions, industry, road dust, construction, burning of waste, stubble burning, biomass burning for cooking, diesel generators, residential emissions and power plants.

UrbanEmissions.Info combined officially available information and its modelling studies to infer that the share of vehicular exhaust to Delhi’s ambient PM2.5 pollution is up to 30%, soil and road dust is up to 20%, biomass burning 20%, industries up to 15%, diesel generators up to 10%, power plants up to 5% and notably, the share of pollution from outside Delhi’s urban airshed (like stubble burning in neighbouring States) is up to 30%.

Multiple researchers have noted that the policy approach and measures taken by Central and State authorities for specific polluting sectors over the years have been fragmented and often reactive.

IIT-Bombay professor Vinish Kathuria noted in the Economic and Political Weekly that the 2002 public transport overhaul to CNG did not yield the desired results. While SPM and PM10 levels fell only marginally, carbon monoxide levels increased.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s 55,000 cap on two-stroke auto rickshaws in 1997 was not revised till 2011. During this time, four-stroke engines were introduced and conversion to CNG was ordered. However, since the cap on the number of autos was in place, this sector could not grow, leading to black marketing of permits. Studies note that between 1997 and 2011, Delhi’s population grew by 45% and registered cars and two-wheelers grew by 250%, meaning the lower availability of autos could have likely contributed to increased private vehicle ownership. Besides, Delhi still does not have the required public bus fleet vis-a-vis demand.

Researchers have also noted challenges with newer policies like the odd-even rule applying to private vehicles. A study by IIT Delhi’s Rahul Goel noted that although vehicular emissions contribute 25% to Delhi’s PM2.5 levels, passenger vehicles contribute just 8%, of which cars constitute 5%. This means that if all passenger vehicles within Delhi stopped operating, PM2.5 levels would reduce by an average of 8%, but the remaining 17% is contributed by heavy freight vehicles which are not covered under the odd-even rule.

Experts also point out that a coordinated response factoring in Delhi’s waste management has to be taken to reduce air pollution. While the daily waste generation rate in Delhi is over 10,000 tons, the capacity of its already overflowing landfills to collect and manage garbage is under 6,000 tons. This leads to the practice of burning waste around residential areas. Reports show that garage is also burnt illegally in landfills when curbs are in place.

One argument for the failure to tackle Delhi’s pollution problems is that a large proportion of these polluting sources are present all year round and high pollution levels are witnessed in winter months due to unfavourable meteorological conditions, meaning stop-gap and seasonal measures often yield unsatisfactory outcomes.

As for the burning of farm residue or stubble in Delhi’s neighbouring States— Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan— researchers have emphasised the need for airshed management, along with improved machinery subsidies from the government and alternatives to crop burning. An airshed is a common geographic area where pollutants get trapped.

Delhi falls in the Indo-Gangetic airshed, which, in Indian territory, includes Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Haryana, Bihar and West Bengal. As per a 2019 study, about half of Delhi’s PM2.5 weightage comes from Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. An airshed management approach would require coordinated responses from States.