Artists and writers have been redoing the classics for a long time, and whatever the result, it ends up fulfilling one important task: keeping the original alive, and ensuring its popularity. There have been many retellings, for instance, of the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, Homer’s The Iliad, set during the Trojan war, and The Odyssey, woven around the journey of Odysseus’ back home after the war, Shakespeare’s plays and the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens or of the Russian masters Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Anton Chekov.

In her latest novel, Demon Copperhead (October, 2022), the American writer Barbara Kingsolver takes Dickens’ novel David Copperfield and gives it the Appalachian makeover, placing the story of the protagonist amid the grave opioid crisis that has gripped America. Set in the mountains of southern Appalachia, it’s the story of a boy, Damon Fields, who is called Demon with a nickname Copperhead because of his hair colour, born to a teenaged single mother in a trailer, dirt poor and no riches to write home about. In her hands, David Copperfield’s opening lines — Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. To begin my life with the beginning of my life, I record that I was born (as I have been informed and believe) on a Friday, at twelve o’clock at night. It was remarked that the clock began to strike, and I began to cry, simultaneously — becomes “First, I got myself born.”

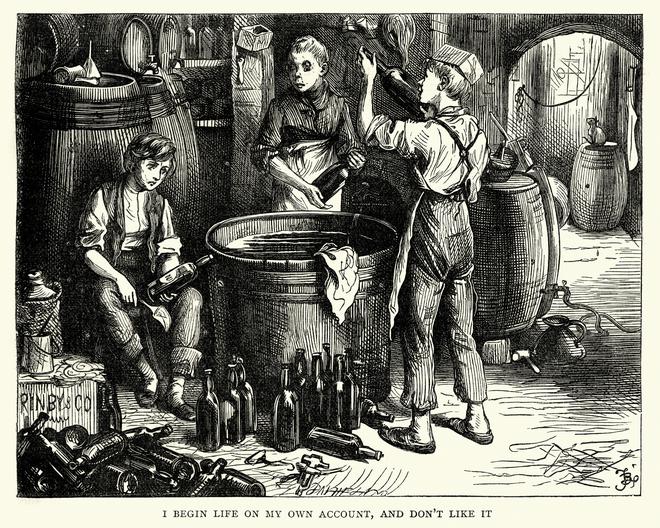

This pithy line is followed by: “A decent crowd was on hand to watch, and they’ve always given me that much: the worst of the job was up to me, my mother being let’s just say out of it.” Kingsolver makes clear her intent from the outset, by choosing these lines from Dickens for the epigraph: “It’s in vain to recall the past, unless it works some influence upon the present.” Damon will be made to brave the perils of foster care, child labour, bad schools and other crushing experiences as a larger crisis of addiction plays out all around him in Lee County, Virginia. “Kid born to the junkie is a junkie. He’ll grow up to be everything you don’t want to know….Anybody will tell you the born of this world are marked from the get-out, win or lose.”

If you know the David Copperfield storyline, Damon will go through it all, the tragedy of having a weak mother, a dead father, a horrible stepfather, a terrible time in school, and yet he will be helped by some friendly outsiders, some not so kind, and then settle down to a family life with some semblance of normalcy. Did he turn out to be a hero like David Copperfield? Well, the fact that he survives against all odds makes Damon Copperhead a heroic figure indeed.

For the Hogarth Shakespeare project, where several writers were asked to revisit a Shakespeare play in the form of a novel, Canadian writer Margaret Atwood picked The Tempest. She called it Hag-Seed, one of the names Prospero uses when he is cursing at his enslaved so-called monster, Caliban. While Jo Nesbo redid Macbeth, Anne Tyler took on The Taming of the Shrew and so forth. “Having grabbed it [The Tempest], I had misgivings… he is mercurial, many-layered, universal in his empathies, slippery as an eel, and a notorious shape-shifter, taking on fresh forms and variations and interpretations with every new production and in every new age,” says Atwood in her essay ‘A Tempestuous Love Story’ (Burning Questions). Yet, she decided to carry on because Shakespeare himself had been a “well-known re-formulator of previous stories and plots.” She sets Hag-Seed in the year 2013, in Canada, as the world witnesses restrictions of freedoms, and it opens with prisoners watching a video of The Tempest that’s been made by some of them. Suddenly, a riot erupts, and the prison is in lockdown. The backstory revolves around the clash between Felix Phillips, a director of a famed theatre festival, who was ousted by his deputy, Tony. Felix has gathered all his enemies in a prison where he had taken a position as a drama teacher and stages The Tempest, hoping to entrap and enchant them and “get both his revenge and his old position back.” Though Miranda — Prospero’s daughter in the original — is dead in Atwood’s novel, she is now a ‘spirit-girl’ who joins in on it. “The play is about illusions… it’s about vengeance versus mercy…. But it’s also about prisons. When you come to think of it, just about everyone in the play is imprisoned one way or another at some moment in time,” says Atwood, and that is why she set it in a prison.

Just this year itself, there have been several reinterpretations of the classics with Zimbabwean-American writer NoViolet Bulawayo redoing George Orwell’s Animal Farm to explore happenings in Zimbabwe after the fall of long-time ruler Robert Mugabe. Her new novel, Glory, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is set in the animal kingdom of Jidada, where ‘Old Horse’ and his wife ‘Marvellous’, a donkey, are ousted in a coup. In the aftermath, there is joy and then despair as things appear to return to chaos. Will a young goat named Destiny be able to bring back hope?

All these novels help to stretch the longevity of characters, from David Copperfield to Prospero (just like Ebenezer Scrooge or Hamlet or King Lear and others). They may be “detached from the story” of their birth but they urge new readers to discover both the original and the reimagined books.